Roger Ballen | Interview by Vice

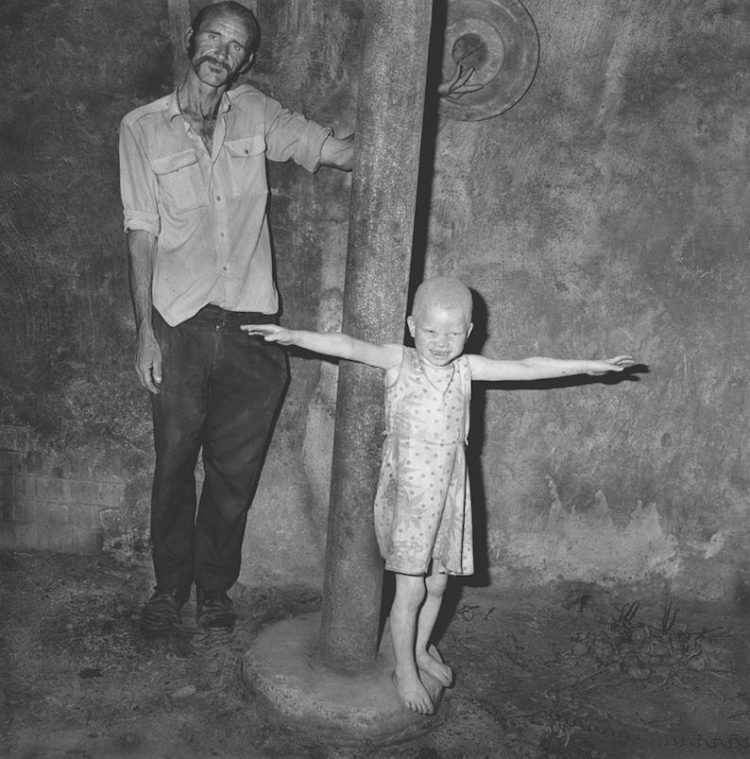

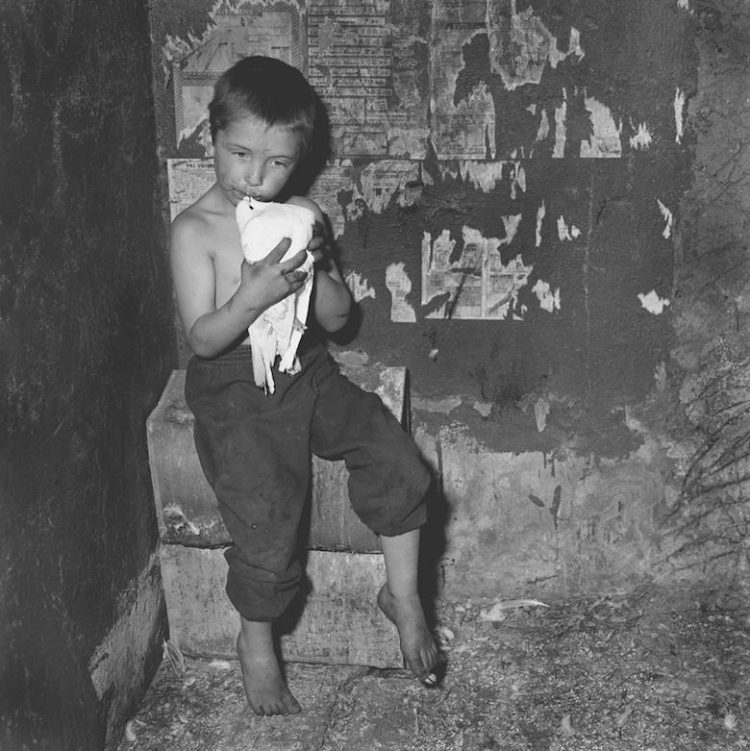

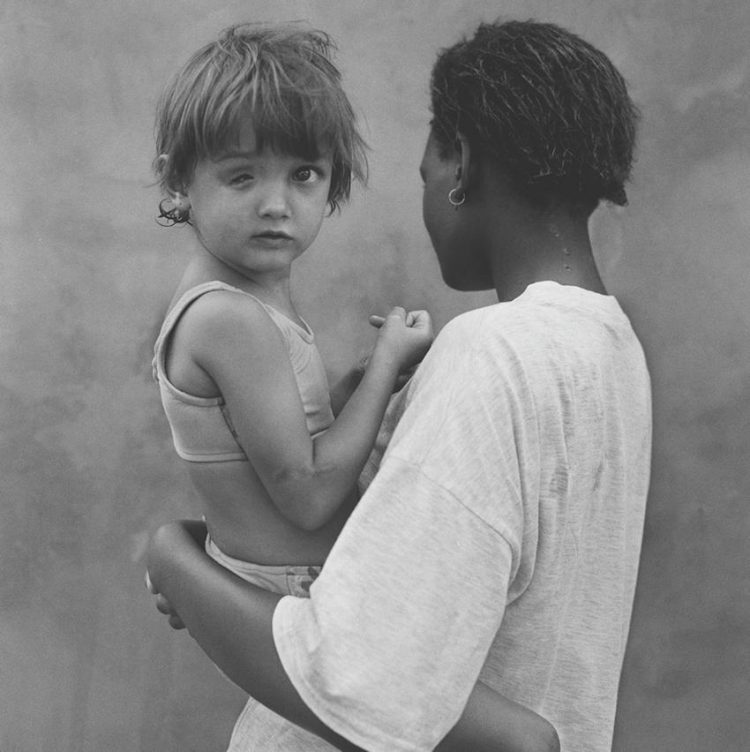

When Die Antwoord's video for "I Fink U Freeky" came out a couple of years back, a whole new generation was introduced to the dark genius of Roger Ballen, the influential photographer who co-directed it, and who has spent the last 50 years immortalizing the fringes of South African society on film in striking black and white images.

Capturing subjects who are often mentally ill or violent, his work has incited admiration and indignation in equal measure; is he exposing truths or being exploitative?

Ballen insists his work says more about the psyche of the viewer than those he photographs. Brought up on a cultural diet of Samuel Beckett and André Kertész, he shuns such socio-political ideas in favor of existential ones. Nowhere are such ideas more prevalent than in Outland, a collection of images that merge naturalistic portraiture with compositional absurdities.

I rang up Roger Ballen to find out more ahead of the republication of this seminal work, and the release of Roger Ballen's Outland, the four-minute film that accompanies it (which you can check out below).

VICE: Hi, Roger. So, how did you get into photography?

Roger Ballen: My mother worked at Magnum Photos in the 1960s and then she started a famous photo gallery in New York in the early 70s, but unfortunately passed away in 1973. She bought me my first camera when I was five. Then, when I graduated from high school in 1968, my parents gave me a Nikon STN and that week I went out like a bullet, taking pictures and trying to emulate some of the famous photographers my mother worked with.

It's interesting that you went out to try and emulate other people, because you've got such a distinct style.

It didn't start that way. My style evolved over decades. In the early years, I didn't have the conceptual ability to learn my own style. You try to emulate people and then if you're fortunate enough you start to develop your own style, but that takes years and years of work.

Why do you choose to shoot exclusively in black and white?

To me, color is confusing. I still enjoy black and white and I'm still learning from black and white. I like the clarity and minimalism of it. I feel that I can make more pertinent statements in black and white.

You typically photograph people who are on the fringes of society in Johannesburg. Do you think your photos are empowering or objectifying?

If Picasso painted me, it doesn't necessarily mean it's me. It's Picasso. The photograph has to be seen more like an aesthetic vision of myself, using the world around me. It's ultimately a transformative process, so I wouldn't think of it as empowering or anything. It's doing nothing, just creating another reality. That's it.

How do you get into contact with the people you photograph?

Sometimes you go to the same house 50 times and people come in and out, sometimes you walk along the street and people start talking to you. You just have to be open and friendly with people and I always try to give back, whether it's a picture, food, money, or medicine. People can say I exploited them, but nobody knows my relationship with the people.

If there's no relationship there, I'm going to get killed. Johannesburg has one of the top murder rates in the world; these places aren't intrinsically friendly. If these people don't like you, and you're carrying all this equipment, you're just going to get in trouble.

True. You provide little narrative to your photographs, particularly inOutland, so they seem quite absurd because they don't have any context...

It becomes universal. If you take the cultural context away, then maybe anybody can relate to it as an image that transcends time.

Are you trying to make people relate to these images, then?

The thing is, my pictures are very formalistic. If you look at the man with the pig, the pig is just as important as the man and the marks on the wall are just as important as the pig. Everything is there for a reason, like anything organic in the world. I think the pictures force people to relate to themselves rather than the subject.

My art has always been psychological of nature, it's not social or political or cultural. That's never been my real purpose, even in the early days. I'm not trying to make a political point. If you can't identify with a picture, you walk away from it. The pictures in Outland, for whatever reason, got into people's heads and they influenced their emotional states somehow or another. Nobody can quantify any of this stuff. Who knows?

What would you say is your most memorable photo shoot experience?

I've been doing this for so long that there are too many to judge. But there's a famous picture called The Cat Catcher. I've known this guy for 20 years and he walks around and steals cats and walks around with them in a bag. I sometimes pick him up and take him to the city where there are witch doctors and he puts the cats on the scale and gets paid per kilogram of cats. Then at the back of the witch doctors' houses they kill the cats then they cut off their ears and paws and the fur and use it for witch doctor medicine.

What about working with Die Antwoord? Music videos are a very different medium to your usual work.

They were very disciplined and organized. They appreciated what I was doing, and felt I was responsible for what we achieved at the time. There was a time when they knew more about every picture I took than any gallery that I'd worked with in the world. I considered it a challenge and I'm happy I did it. Especially as the number of people who are interested in music videos is ten thousand times bigger than those interested in serious black and white photography. So many people got to know my photography through that video.

Would you say that, because the art business is smaller in Johannesburg than in New York, for example, it has helped you as an artist?

Yes. What's been most important here in terms of my own work is the isolation here. People say, "What inspires you?" and I always say, "The white wall in front of me." I don't need inspiration, I just need to be passionate about what I'm doing, disciplined, focused, and committed. There's this idea that you have to go to every museum and read every book but all you have to do is find out what's important to you and find a way of expressing it and continually work at it.

You've been doing this for so many years now. You must have seen the art world change drastically in that time.

Like everything else in life, it's positive in some ways and negative in others. There are more people interested in art, but the standard is very confusing and hard to evaluate. It's become a business rather than a business of poetry. A lot of the negatives are the marketing, pricing, and celebrity nature of the business. The spirituality has been lost in the dust, in my personal opinion.

Can you tell me a bit about this new film you've made, Roger Ballen's Outland?

I worked with the same person that I worked with in Asylum of the Birds, who I sent to the Outland to meet some of the people I've worked with. He eventually meets this guy who spends most of his day going out and catching rats. He walks around with these rats and goes to this house and then he lets the rats out. We follow him around a bit.

Parallel to this, some months ago another person we met got attacked with an axe and he got 36 axe chops on his body, including his head. They thought he was dead. We follow him around a bit as well, and since the attack he's become super aggressive, chopping everything up. He has a habit of catching animals and he chops them to death. He wants to get back at the world. Fortunately, he hasn't tried to chop somebody else up but maybe that will happen next.

Thanks, Roger.

(source: Vice Magazine)