‘I never wanted to shoot another pop star – I was tortured by them’ | Interview David LaChapelle | The Guardian

His lurid aesthetic shaped the celebrity age, but 11 years ago LaChapelle escaped to a farm in Hawaii. He talks about his journey from 14-year-old gay runaway in Warhol's New York to enlightened 'Grandpa Moses of photography'

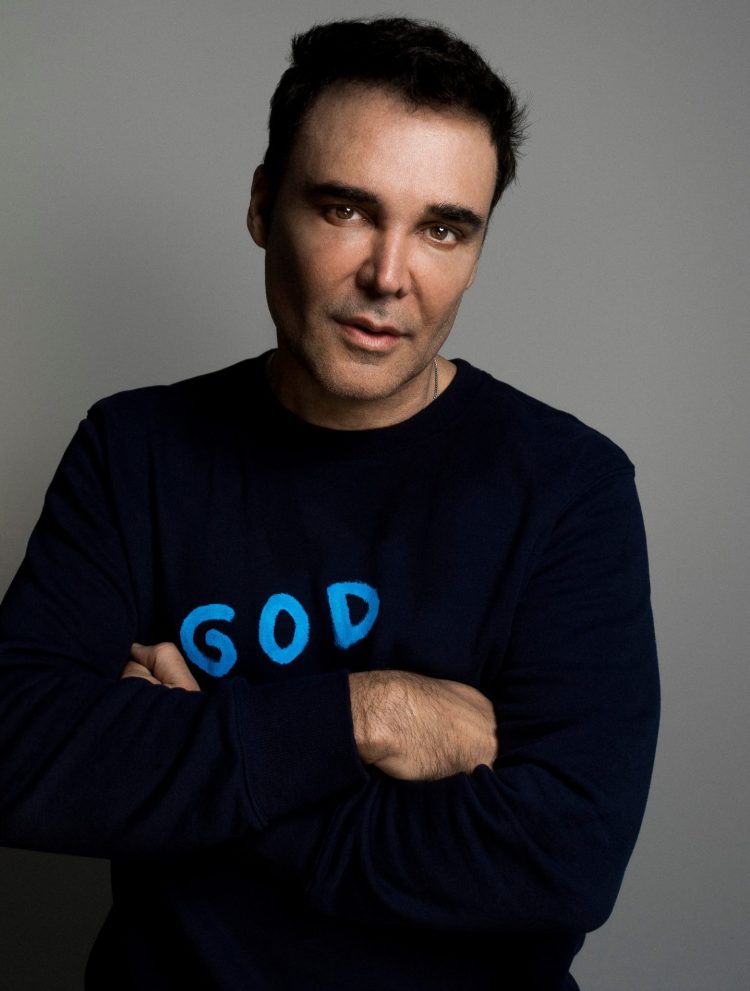

The evening before we are due to meet, David LaChapelle spends several hours greeting fans and signing books in Berlin. The queue snakes outside his publisher Taschen's bookshop and down the street. One woman, a middle-aged artist, bares her breasts for a photo with him. Another gets her wrist signed and returns later to show she got it tattooed. The next afternoon, LaChapelle, no stranger to daft behaviour, can only shrug, touched but baffled. He wasn?t sure there would be interest in this comeback; his two new anthologies are going to be his final books. This is it, he promises. An edit of unseen photos from his 30-year career as one of the most striking and controversial chroniclers of pop culture.

'For a long time, I worked non-stop,' he says. 'I had to always have three magazine covers, a music video in the Top 10 of [MTV chart show] TRL, one of the Vogues happening or I'd be forgotten and irrelevant.'

LaChapelle dials the conversation to the tone of a therapeutic confessional, which is perhaps encouraged by the fact that we are sitting together chatshow style: sloped towards each other in plush velvet armchairs on the stage from last night's signing. 'It's a paradoxical place to be, working for magazines that push the idea that happiness is going to come with the next purchase and new season of merchandise,' he says quietly. 'I love glamour and fashion and beauty - that has been with civilisations for ever, but I needed to get away from the propaganda of that. When I quit everything, I never wanted to shoot another pop star as long as I lived, I was tortured by them.'

It has been 11 years since LaChapelle, 54, swore off the celebrity circuit to retreat to rural Maui, Hawaii, and reinvent himself as a farmer. At the peak of his output from the mid-90s to the mid-00s, LaChapelle's visual signature - lurid and dramatic, beautiful and grotesque - popped from every angle of culture. His works in film and photography revel in super-high-end production values, where his immense perfectionist attention to detail changed the size and scope of what a celebrity photoshoot could be; he elevated it to an art form that has been endlessly mimicked since.

He directed Madonna through her Ray of Light years (and later quit by hanging up the phone on her); Michael Jackson was a close friend; Andy Warhol was his mentor. Everyone worth their salt - from Tupac Shakur and Leonardo DiCaprio to Hillary Clinton and Lady Gaga had their most zeitgeisty moment captured by him. He shot Marilyn Manson as a lollipop lady and Kanye West as Jesus. He helped Christina Aguilera and Mariah Carey reinvent themselves from prim pop princesses to OTT saucepots. Part Renaissance painter, part Jeff Koonsian kitsch, LaChapelle on form produces works that are stunning, witty, ironic and clever.

'But this industry is no place to get old,' he says, with a hollowed-out zen. 'I'd seen the circle around Andy [Warhol] come and go, the phoniness of people who surrounded him. At the time, Andy couldn't sell a single artwork to a gallery, the art world in [the US] really dismissed him. All he wanted was a show at the Museum of Modern Art and they never gave him one when he was alive.' LaChapelle was hired by Warhol for Interview magazine in the early 80s when he was still a teenage runaway in New York, blagging his way into Studio 54; he was the last to shoot a professional Warhol portrait in 1986. 'When Andy died two years later, they finally gave him the biggest show in the museum's history.' He shakes his head. 'God.'

Has it made him wary?

'I'm not one of those people that sees the bad in everyone, but I definitely take my time with people. In the studio I have in Los Angeles, we have lots of young interns - they've been invaluable at putting together these books because I started seeing [the work] through their eyes.' He doesn't do Instagram or care much for social media because it is 'just another way to be busy without really doing anything', plus his fans do it all for him anyway. 'I'm like Grandpa Moses of photography, giving them advice.'

Conversations with his young team, he tells me, keep forking to sexuality and gender at the moment. 'We're living in such a puritanical moment right now when it comes to sex.' Is he referring to photographer Terry Richardson? 'I don't know Terry's work...' I think he is being disingenuous. There is a 'but' coming and, for a moment, I wonder where this riff might go. 'But, I know there has to be respect in all industries. People in power - you don't have sex with an intern! I would get in a lot of arguments with people at the time about President Clinton. He really did demoralise the Democratic party. Bush would not have been able to steal the election had Clinton not have done that. And if you have it in the highest level of office, you're going to have it everywhere people are in power.'

What does he make then, of the domino effect playing out and toppling some of these people in power? 'It needs to be called out. At the same time, the sort of joy people take in the takedown is something we have to look at as a culture. We have to be careful about the glee in vigilantism.' Lines are being redrawn, he says, quicker than people are processing the information.

'I listen to a lot of Camille Paglia, only because she is such a different voice. You have to read what she says about [transgender issues] right now and the fall of civilisation. But, she says, people who in the 60s, say, who didn't fit and who were beatniks, might today have considered themselves transgender. It's another expression of being anti-mainstream.' LaChapelle doesn't agree entirely with all Paglia says, but is all for nonconformist streaks and discussion around identity; he made a star of Amanda Lepore, one of the first transgender models and performance artists, and his muses (Lepore, Daphne Guinness, Pamela Anderson) all share a cartoonish quality that he renders fantastic and beautiful.

'Amanda had to really fight to get her surgery and become her. I mean, I went through an androgynous period when I was 11 or 12 and I'm glad the option wasn't out there for me to get hormone blockers. I don't know what I would have done, I was a little bit nuts. But it's not something we should just be able to order off a menu.' LaChapelle is talking, he says, from considered experience. 'I think that if someone is feeling this way, they really need to speak up and believe it and fight for it a little bit because you can't go back - I know at least two people who tried to.' He pauses. 'Becoming trans has almost become a little bit fashionable in some places. And that's worrisome. It's like: "Are you sure? You're kind of young, maybe wait before you do some body altering." Also, it's not gonna make your problems go away; you're gonna wake up with the same problems - maybe more.'

When he was 22 in the mid-80s, LaChapelle ran away from the death of his boyfriend through the Aids epidemic in New York and landed in a dilapidated south London housing estate. It was the height of Boy George's fame and the young, gay, beautiful, Warhol protege was inducted into the city's gloriously hedonistic club scene, then starring Leigh Bowery and Steve Strange. 'They were so ahead of their time,' he tells me. 'I lived in New York since I was 15, I thought I'd seen it all. When I went to London, the level of creativity and insanity - they were on a whole other planet.' So much so that LaChapelle ended up marrying Marilyn's (female) publicist for a year 'I still don't know how?' and was quickly hired as a photographer by the Face and Vogue.

London was formative in two significant ways. First, because it taught him the importance of originality because 'you didn't copy people. You'd be considered an idiot. LA is the literal opposite.' Second, amid 'the grey, and Thatcher and the coalminers' strike', he developed his unique aesthetic that is still seen everywhere: Beyoncé's Instagrammed pregnancy was glossily LaChapellian (the photographer was one of his former interns); the high street's preoccupation with the dazzle of unicorns, mermaids, rainbows and hyper-saturated colour echo LaChapelle; the very existence of the Kardashians is LaChapelle's subversion of high trash come full circle - he first put Paris Hilton on the map and has since, of course, worked with Kim and Kanye.

'Someone wrote a comment online when I moved to Maui, like: "The person who gave us Paris Hilton and destroyed our culture is now gonna go live in the jungle." Did I really bring culture down?!' Well, didn't he fetishise some of the dumber aspects of it?

'Paris had a charisma back then that you couldn't take your eyes off,' he explains. 'She would giggle and laugh and be effervescent and take up a room. She was desperate to be in my photographs and one day we needed her for a jeans shoot.' The model at the time couldn't fit into the sample size provided and Paris was given a shot. 'She came over, she hadn't been home for, like, three days, but she looked incredible. You never saw that girl looking messed up.' Some people, he says, really do hold an indescribable star quality.

Nonetheless, LaChapelle's shuttling between commercial photography - where he has shot campaigns for brands including Diesel and Coca-Cola - to exhibitions around the world seemed a rare trick back then.

'If you really want to shock people in the art world, talk about Jesus or God,' he says. 'You could take a dump on a gallery floor and they won't care. That's art - when I wanted to do Jesus Is My Homeboy [where he positioned Jesus with pimps, prostitutes and gangsters], I wanted to ask who Jesus would hang with, if he was back. And it wouldn't be the aristocrats or the rich people, but the disfranchised. I was making this point to the editor of i-D and I heard the phone go dead. Eastern religions like Buddhism are cool - anything foreign or exotic like that is acceptable, but Christianity has a horrible reputation because of fundamentalists and evangelicals.'

LaChapelle's faith - which he says never wavered, although he did neglect it - seems at odds with the debauchery and decadence he is known for. He doesn't buy it. 'I believe religions are derivative of truth leading to the same notion. They're guides all our ancestors had for countless generations and the reason has been subtracted from our lives, which has left us with this void that we've filled with materialism.' He pauses and gestures across the shiny piles of his new books stacked around us. 'It will, for sure, turn some people off because they'll associate me with this,' by which I assume he means religion, but I realise 'this' is also the older, wiser, serene version of himself.

It is, in part, a consequence of having to fine-tune his mental health constantly, and the death of his mother (who, he used to say, first taught him photography) a couple of years ago; LaChapelle is bipolar, but antidepressants do not work for him and he needs to monitor his exercise and sleep to stop himself from slipping into an episode. 'You want to ride the part that feels so good because your brain is working fast and ideas come more easily. You have more energy and everything flows, and you're seeing things from a higher perspective,' he explains. A heavy 'but' follows.

'But ... it can switch into delusion and be dangerous. You don't want to be depressed. I've been caught up with the police a few times; I once got beat up outside my own house in LA.' Even then, he says, he could rely on being saved 'because they think he's white, gay, rich, he's probably on crystal meth. It makes you wonder - imagine what black people go through.'

When things really affect him, it's usually because he has looked at the news too much. 'It's not just the news itself, it's the hierarchy. So you will have a story about an atrocity that has happened, next to some terrorism, next to Taylor Swift.' A slip of bitchiness escapes. 'Taylor Swift! I don't even know one person who listens to her, but the point is how are all these stories getting the same play?' It is, he reasons, anxiety-inducing. 'We're on the precipice of so many things we've never had to deal with before as a species. If you took an iPad back in hunter-gatherer times and you showed them everyone that got killed that day in a landslide or beaten to death by the watering hole, they'd have a panic attack as well and not be able to sleep.'

What's the answer? 'Well, I haven't achieved enlightenment,' he laughs. 'But I guess it's balance. We have to get ourselves in alignment.' Does he not miss some of the whirlwind of those earlier chaotic days, the adrenaline? He nods a no. 'You know Epictetus, the Greek philosopher? He's like, we all have a role in life - play your role and live it to the fullest.'

Lost + Found Part I and Good News Part II by David LaChapelle (£49.99, Taschen) are out now

(source: theguardian.com)