Artsy | 7 David LaChapelle Photographs That Reframe Religious Imagery | by Elyssa Goodman

December 5th, 2018

©David LaChapelle - Enquire

Though David LaChapelle became known for his splashy, high-concept images of celebrities—from musician Elton John atop a leopard-print piano to supermodel Naomi Campbell in the buff, pouring milk on herself—an undercurrent of religious and art historical references have always run through his imagery. He is never too far from composing a pietà or casting his own personal Jesus, retelling these age-old stories with the ecstatic splendor that only LaChapelle can conjure, with Courtney Love or Lil’ Kim as the Virgin Mary and Tupac Shakur or Kanye West as the holy son.Even now, as the artist veers away from commercial work, he continues to draw inspiration from religion and the works of the Old Masters, while also unraveling his own interior life. LaChapelle’s most recent monographs, 2017’s Lost + Found (Part I) and Good News (Part II)—which he has said are quite possibly his final volumes—particularly feature these themes. Here, we explore the iconography of LaChapelle’s work throughout the years; some of the works are currently on view at Galerie Templon in Paris and Staley-Wise Gallery in New York.

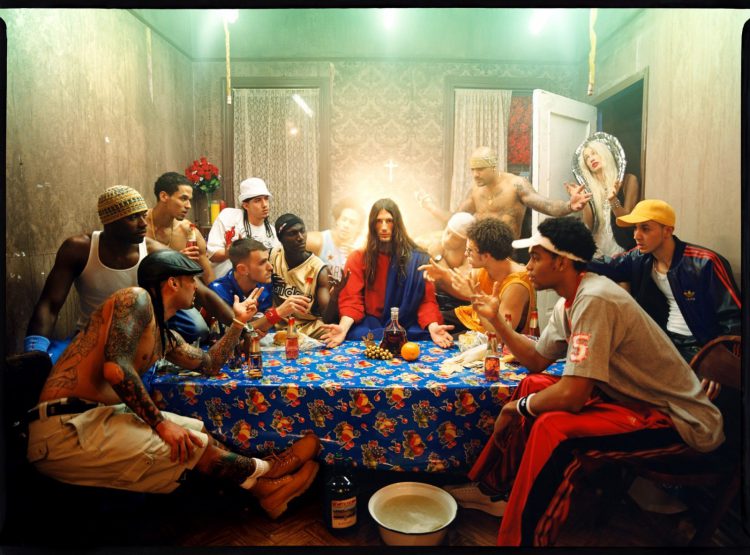

The First Supper (2017) and Last Supper (2003)

© David LaChapelle

LaChapelle’s The First Supper is from his ongoing series “Paradise,” an exploration of heaven and enlightenment pursued in the idyllic natural world. His influences from the French symbolist painter Odilon Redon can be seen in the ethereal, spot-like use of color surrounding the figures. Many of the images in “Paradise” were shot on location at LaChapelle’s property in Maui, adding an Eden-esque appearance to some images.Last Supper, photographed more than a decade earlier, modernized the life of Jesus, taking back religious iconography from fundamentalist thought and grounding it in a more egalitarian mentality. Though the image draws on the classic Leonardo da Vinci painting of the same name, Andy Warhol’s influence is here, too—LaChapelle witnessed Warhol paint his vibrant color version of The Last Supper while under the Pop artist’s mentorship.

Venus of Willendorf (Pink) (2016)

© David LaChapelle

With this image, LaChapelle reimagines the Venus of Willendorf, the limestone figurine considered to be one of the earliest depictions of female fertility ever made. She was found in Austria in 1908, and believed to have been sculpted around 25,000 years ago. The figure, possibly a depiction of a maternal goddess, was said to be covered in a rose tint, which LaChapelle’s version exaggerates in shiny, bright magenta.The original figure was made in an era that prized a heavy frame and reproductive ease; however, she has also been thought to represent the consequences of self-inspection. What could have been the figure’s face is possibly obscured, as if to caution against becoming lost in one’s self. This interpretation echoes personal issues that LaChapelle has publicly discussed in the past, and mirrors the introspection of his later works.

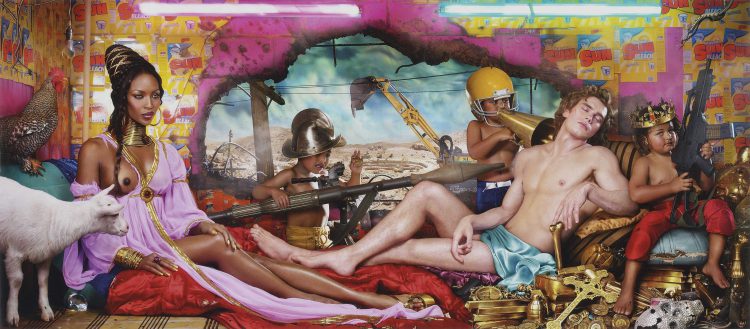

The Rape of Africa (2009)

© David LaChapelle - Enquire

For this tableau, LaChapelle referenced Sandro Botticelli’s painting Venus and Mars (1485) to comment on the exploitation of the African continent. In particular, he had seen National Geographic’s 2009 exposé on the unconscionable effects of the gold trade, and reinterpreted Venus and Marsto tell the story. “It’s a postcoital scene: Mars, god of war, is sleeping on all his spoils, while Venus, goddess of love, is looking unsatisfied,” he toldThe Guardian in 2014. “Things haven’t changed much, I thought. Greed and war versus love and beauty.”Elements from Botticelli’s work took on new forms in LaChapelle’s: Satyrs turned into child soldiers, mines were added to the backdrop, and Venus represents Africa, her dress ripped to denote rape. And, as Botticelli used a well-known beauty to sit for his Venus, LaChapelle wanted to do the same, working again with Naomi Campbell.Ultimately, LaChapelle wanted the image to critique consumerism, greed, and power. “I made it right after the financial collapse [of 2007–08], when we were being advised to invest in gold and gold production spiked tenfold,” LaChapelle said. “The irony is that by putting your money into a safer security like gold, you are ensuring more devastation, more climate change, more destruction.”

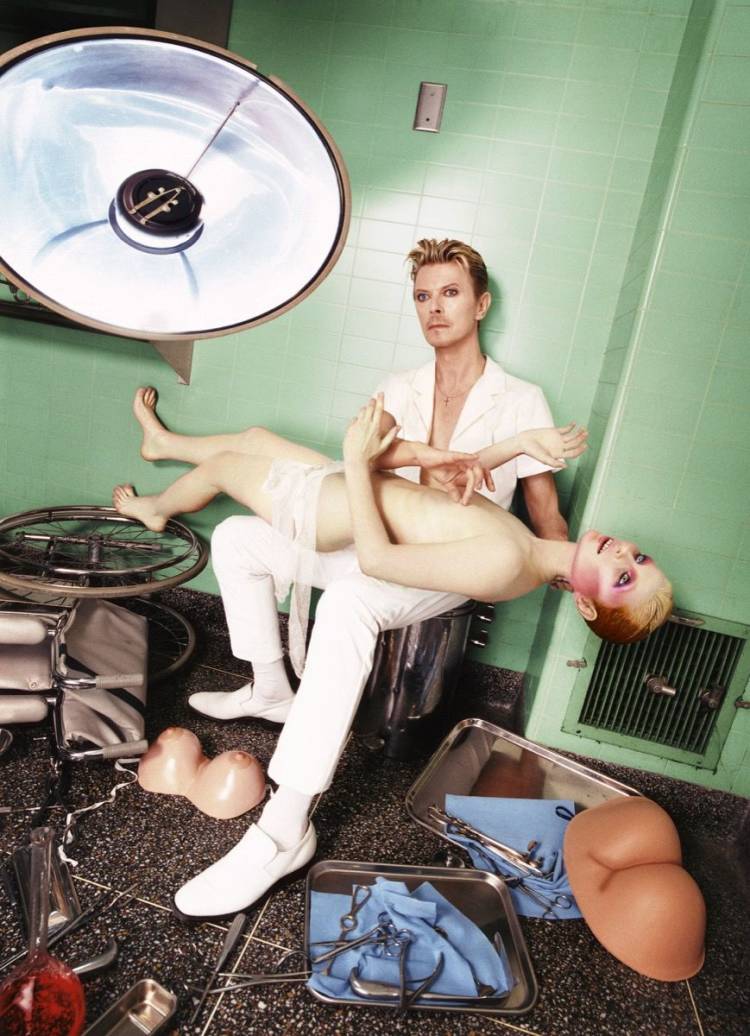

David Bowie: Self Preservation (1995)

© David LaChapelle

While the idea for the image David Bowie: Self Preservation was possibly Bowie’s, LaChapelle acknowledged that the musician’s iterations were so varied that it was inspiring to draw on representations of him throughout his career. Here, Bowie cradles a doll of himself in Aladdin Sane–era makeup that’s not far from LaChapelle’s previous iterations of Michelangelo’s Pietà(ca. 1498–99), even though the photographer’s version featuring Courtney Love bearing a Kurt Cobain figure is a more literal interpretation.The image was taken around the time Bowie was working on his album Outside, a concept album following a narrative of art and murder, and thereby skewed a little darker than LaChapelle said he was normally comfortable with. “I’m more humorous, colorful. The dark thing was never my way, but that’s what he wanted to do,” LaChapelle said of the production. “But it was a very fruitful shoot.”

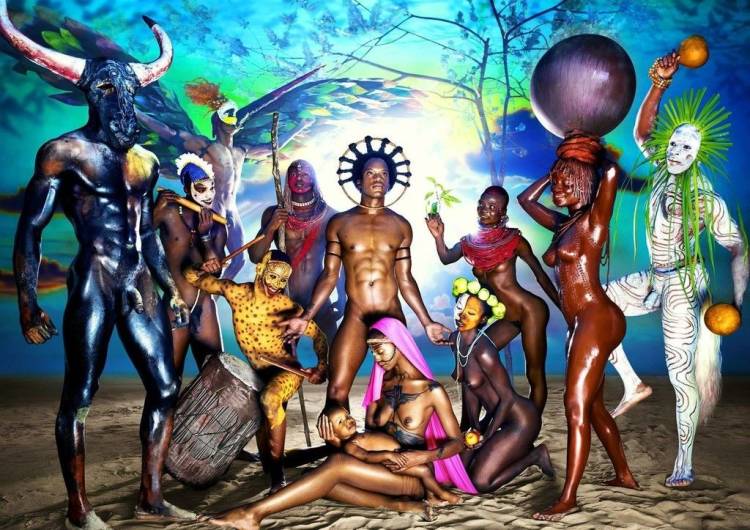

Nativity (2012)

© David LaChapelle

Like many of the great masters, LaChapelle has been inspired by the classic nativity scene. While the artwork of Western religious narratives often glorified the church and portrayed Jesus in a more European mien, LaChapelle reimagines that tradition in this image, set in Africa.Here, the Virgin Mary holds the baby Jesus, sitting on the sand, surrounded by symbolism. In lieu of an ox, which represented patience in the Old Testament, LaChapelle features a man in an ox mask, nodding to the use of masks in religious and cultural ceremonies around the world. A bird replaces the traditional depiction of an angel on the scene, representing fertility, freedom, and the human soul. A leopard, considered to be the animal of a ruler, is represented, too, in the man drumming over the newborn, painted in spots.LaChapelle combines these images with traditional Western biblical interpretations: His shepherd is also cloaked in red—the color of the Holy Spirit—and in the background, there’s a tree, symbolizing the Tree of Life, whose fruits offer life eternal. Like his “Jesus is My Homeboy” series, in this work, LaChapelle altered traditional religious iconography, blending with it symbols that transcend traditional narratives.

Kanye West: Riot (2006)

© David LaChapelle

In 2006, LaChapelle depicted rapper Kanye West as Jesus in a Rolling Stonecover story published that February. In this image, LaChapelle’s depiction of West is practically medieval, placing the Crusades in a modern context: Instead of knights on horseback with shields, there’s a bomb squad holding up shields. During the Crusades, military campaigns were waged to capture Jerusalem, and citizens from across Europe participated in merciless battles in hopes of claiming the Holy Land. In this image, West comes up against the bomb squad raising this red flag, preparing for battle.“[West is] popular music’s martyr,” LaChapelle said. “People are always are slinging arrows at him. He takes a lot of shots.” Martyrdom, choosing to die before renouncing faith, was revered during the Crusades. Likewise, West himself would choose to become a cultural pariah before abandoning his artistic goals.

Behold (2017)

© David LaChapelle

LaChapelle’s dreamy 2017 image Behold covered his book Good News (Part II). A man, painted turquoise, stands with his eyes closed, a crown of flowers on his curly hair, rays of light beaming from behind him. The entire book features a wealth of religious symbolism, so it’s no surprise Behold is similar to Renaissance depictions of Jesus, with halos encircling his head. Behold is a revamped version of these portrayals, done up with LaChapelle’s highly saturated, electric vision. There’s not only bold color—a departure from the darker Renaissance palette—but streams of light that look almost neon in nature. “I was always interested in the miraculous realm of being, not just the material realm, and trying to photograph the un-photographable,” LaChapelle told Garage in 2017. “The mystical is interesting to me.”

Source: Artsy